TechBio's California Roll Moment

Notes towards a new industrial revolution for pharma

Eli Lilly was founded in the wreckage of the U.S. Civil War. Colonel Eli Lilly, a chemist turned Union officer, returned from battle determined to bring scientific rigor to medicine in a time when cures were often superstition and luck. His company was built in the 1870s on discipline, experimentation, and a new kind of industrial trust. A company that said science could be organized, standardized, and scaled, so that patients could trust the output. That really is what the modern pharmaceuticals are: trust manufactured in the form of a pill. The trust that that pill works, or is at least, safe. For more than a century, the Eli Lilly model defined modern pharmaceuticals with its biggest invention: industrial trust in pharmaceuticals.

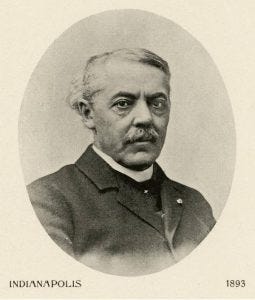

Colonel Eli Lilly, Indianapolis (1893)

The birth of biotech

The first great wave of modern biotech came in the 1980s, when companies like Genentech and Amgen first turned biology into engineering. Think recombinant DNA, monoclonal antibodies, genetically modified cells. The second wave came in the 2000s, when genomics, computation, and venture capital collided: sequencing costs fell, startups multiplied, and biotech turned moonshot science into moonshot startups. Yet today, that biotechnology world is showing its age. Drug approvals have slowed, the cost of development has skyrocketed, and the system built by scientists and financiers alike has begun to strain under its own complexity.

TechBio, the California Roll we have all been waiting for

The next renaissance will not come from biotech as we know it, but from TechBio and AI for Bio. The merging of artificial intelligence and life sciences.

TechBio will be like the California roll: it took Californians to flip sushi inside out and create something that the Japanese themselves had not dared to do. In the same way, it will take technologists to reimagine how biology is built; to break old taboos, automate what was once artisanal, and make medicine scalable, flipping Biotech into TechBio.

At the time that the California Roll was invented (1967), turning sushi “inside out” was considered a taboo in Japan, breaking the tradition hat had defined centuries of sushi.

Lessons from software

Twenty years ago, software looked like biotech does now. It was expensive, slow, and controlled by incumbents. The early software world was MBA-led, not founder-led; investors incubated their own companies, hired their own CEOs, and treated devs as replaceable labor. Then came open-source software, cloud infrastructure, and global distribution. Two cofounders in a dorm room could suddenly reach the world. The barrier wasn’t capital; it was creativity. Once cost fell and access widened, founders took control. Even in regulated industries like finance, entrepreneurs broke through. PayPal and later Robinhood proved that even in highly regulated domains like finance, technology could advance.

So where is the PayPal of pharma? Where is the founder-led company that rewires how medicine is developed and tested? It doesn’t exist yet, because the cost of biotech entrepreneurship hasn’t dropped to levels of software yet. Biotech remains in its pre-cloud era: pharma-led, capital-heavy, and risk-averse. Most “startups” are still conceived in venture studios, built by hired executives, and run under investor control. That model was somewhat justified when trials cost millions. It doesn’t work now. Trials now take 10 years, $1 billion, and succeed less than 10% of the time to produce a new therapy.

The acceleration

The change biotech needs is the same one that transformed software: the collapse of cost and complexity. As long as each trial, experiment, and regulatory cycle becomes more expensive each year, no founder can move fast enough to challenge the system. The revolution will come from making the process itself cheaper, faster, and smarter; turning biology into an engineering problem, not a bureaucratic one.

The first signs of this are already visible. Biology is becoming computational. At Profluent, new proteins are designed and tested entirely in silico. Genesis Therapeutics uses graph neural networks to model molecular behavior. Xaira Therapeutics generates drug candidates nature never imagined. In the clinical layer, Formation Bio and Reify Health are rethinking trials as intelligent, adaptive systems. These companies are early prototypes of TechBio: small, technical, founder-led.

Clinical trials hold the answer

Today, the bottleneck remains. Founders can now create brilliant molecules in weeks. Yet it still takes years to prove them. The clinical trials phase is where most innovation dies. Everyone is betting on AI for drug discovery, and that bet is simple: that intelligence can compress the search space for new molecules. But good molecules, and even great ones, still fail in clinical trials. They fail not because they are wrong, but because the trial is. Design flaws, patient selection, operational noise, and unobserved biases destroy billions of dollars of potential. What is missing is another layer of intelligence. An intelligence not focused on discovery only, but on delivery; not on the molecule, but on the path that brings it to patients.

Software became founder-led because it became easy to build and test ideas. Biotech will become founder-led when it becomes easy to run and validate them. Once experimentation is cheap enough and trials are intelligent enough, small teams will be able to build, test, and iterate in medicine as fast as they do in code. This is the task of the PayPal of pharma, the company that rewires the system from the bottom up by making it ten times easier to build within it.

Intelligence for delivery, not just discovery

What if a company was built entirely focused on developing Clinical Trial Intelligence?Building an AI layer that increases the success rate of clinical trials and helps decision-makers see what’s coming before it happens? An intelligent clinical trial can predicts trial outcomes, identify failure risk early, and enable sponsors to intervene in trial design and operations in real time. By connecting biological insight with operational foresight, Clinical Trial Intelligence would help pharmaceutical companies develop drugs more intelligently, efficiently, and successfully.

The cost curve will bend. It always does. Computation has already rewritten discovery. Automation is beginning to rewrite development. A new company will emerge to rewrite clinical trial validation, which is the hardest and most expensive phase of all. The next generation of founder-led biotech will not just make better drugs; it will make smarter ways to prove they work. When that happens, biology will finally catch up to software; not by imitating it, but by becoming it.

In 1998, the future of finance looked less like Bank of America in New York City and more like PayPal in Palo Alto. In 2025, intelligent pharma looks less like Eli Lilly in Indianapolis and more like a young startup in Mountain View.

Disclaimer:

This essay is an educational and speculative exploration of how a company might be founded in today’s technological landscape. All references to Eli Lilly are for historical and illustrative purposes only. It is not affiliated with, endorsed by, or representative of Eli Lilly and Company or any of its employees, subsidiaries, or affiliates. Or any company mentioned in the article.