Is it too early to prepare for the next pandemic?

No. We must act now. AI can harm. AI can help.

Next week we will release our findings on humanity’s pandemic risk from our perspective, deploying clinical trial intelligence to analyze not only the likely disease vectors, but what trials are running now to meet the future need. We will publish the ongoing trials and our risk analysis.

Our effort comes from a question. Is it too early to prepare for the next pandemic? “What pandemic are you talking about?” is a fair question. I’m talking about the next one. The big one.

The Next Pandemic

We do not know its exact form yet, but we know its general outline. The pattern is familiar. The pressure is rising. Viruses cross into humans all the time; most fail, some linger, a few adapt. It takes only one with the right properties to set the world on fire. It could be another coronavirus, a Covid 3, produced by the same evolutionary engine that gave us SARS in 2003 and COVID 19 in 2020. It could be a new respiratory RNA virus that moves efficiently through air and aerosol, the kind that spreads before symptoms appear and punishes any delay in detection.

It will almost certainly be viral, not bacterial. Bacteria announce themselves. They are slower, heavier, easier to treat. Viruses slip through surveillance. They mutate fast. They exploit our mobility, our density, our networks. It will almost certainly be zoonotic. That is how pandemics begin: the boundary between humans and animals thins, a virus jumps, adapts, learns the human body, and then learns how to move from one human body to the next.

It could be a novel influenza A strain from the H5, H7, or H9 lineages, the strains we monitor constantly because they look like threats waiting for an opportunity. It could be a paramyxovirus like Nipah or Hendra, both capable of high mortality and silent spread before symptoms. It could be an arbovirus like dengue or Zika, which already move through massive populations and could evolve into more efficient respiratory or vertical transmission.

These possibilities are not remote. They are not speculative. They are not doomsday fiction. They are the baseline. The world now lives in an era where spillover events happen more often, climate pushes species together, and global travel turns a single infection into a global footprint within days. The next pandemic is not a surprise. It is a schedule we have not seen yet.

The Missing Quadrant

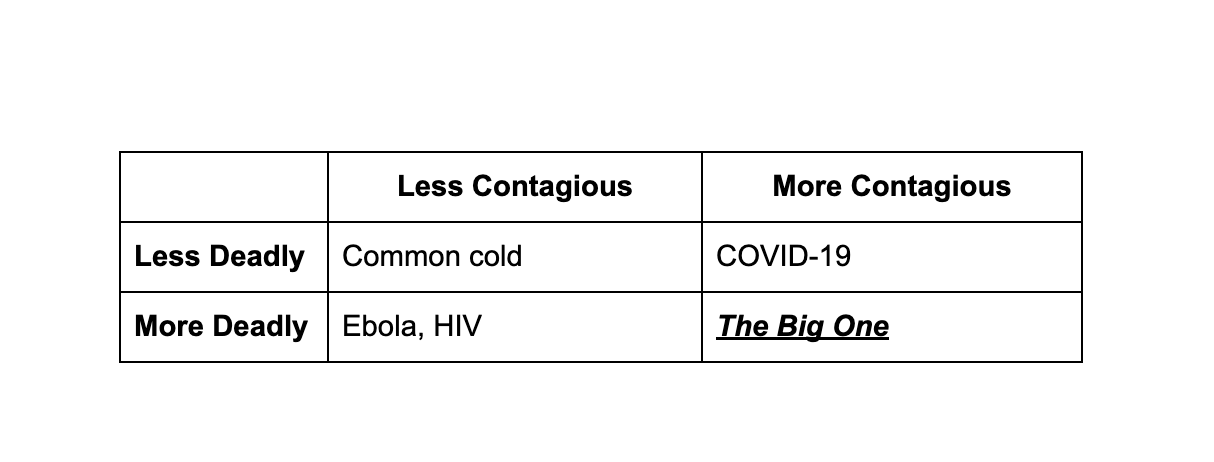

We were fortunate during COVID 19. It was highly contagious but less deadly. Ebola is the mirror image: highly deadly but not very contagious. The catastrophic quadrant is the one we have not experienced.

The Big One

A virus with the transmissibility of Covid and the mortality rate of Ebola, or HIV, would be an event of global destabilization, a billion deaths in a single arc. The bubonic plague scaled to a connected world. An airborne HIV.

Pandemics usually begin with a simple and brutal truth. Viruses mutate at random. Most mutations do nothing. Some weaken the virus. A few give it an advantage. When those rare mutations appear inside an animal host and allow the virus to jump species, we get zoonotic spillover. Bats, birds, pigs, primates, and countless other reservoirs carry vast viral libraries that evolve constantly. When a mutation gives a virus the ability to enter human cells, replicate efficiently, or spread through respiratory droplets, the spark is lit. The jump is accidental. The consequences are not. This is how pandemics start.

Another new and deeply concerning pandemic risk is the possibility of human designed viruses created with the help of advanced AI systems. The danger is not that AI magically invents pathogens on its own, but that it can accelerate scientific workflows, lower barriers to complex biological design, and help inexperienced or malicious actors navigate what used to be extremely difficult steps. This creates a world where tailored viruses could, in theory, be engineered with properties that natural evolution rarely combines at once: high transmissibility, delayed symptoms, immune evasion. As AI becomes more capable, society must treat engineered pathogens as a new class of threat, one that arises not from random mutation or animal spillover but from human intent amplified by powerful tools. Even discussing this requires great care. One should not in detail describe methods, but rather name the risk clearly. But this must be discussed. Another essay in the near future will be published here. This essay however, focuses on pandemic responses and what clinical trial intelligence could mean in preparing for the next pandemic.

The World in 1918 vs 2020

The Spanish Flu of 1918 lasted nearly two years. It infected half a billion people and killed tens of millions. No vaccine existed then, not during the pandemic and not for decades afterward. The scientific world of 1918 had never seen a virus under a microscope. The electron microscope would not exist until 1931. Many scientists targeted “Pfeiffer’s bacillus,” believing incorrectly that a bacterium caused the disease. There were no genetic tools, no cell culture, no antivirals, no antibiotics, and no real virology. World War I dismantled laboratories and public health infrastructure. Humanity faced a virus of extraordinary lethality with almost no understanding of what it was fighting.

A century later, COVID 19 unfolded in a world with a completely different scientific arsenal. Chinese scientists sequenced the SARS COV 2 genome within 48 hours and posted it publicly on January 10, 2020. mRNA vaccine design began that same weekend. Two decades of platform work on lipids, mRNA stability, and earlier coronavirus vaccines suddenly activated. The global scientific machine spun up: billions of dollars, thousands of trial sites, rolling reviews at the FDA, real time data infrastructure across continents. It produced a vaccine in eleven months, the fastest in human history. It was astonishing. And still, the process was messy.

Complexity

Trials chased a moving virus: Wuhan strain, then Alpha, then Delta, then Omicron. Every shift changed the underlying biology of the target. A vaccine trial designed for one variant would face a different one by the time endpoints arrived. Human immune systems layered more variability on top: age, conditions, genetics, prior infections, behavior. Trials required real infections to measure efficacy, which meant sites had to follow the geography of outbreaks in real time. Ethics demanded that placebo participants be vaccinated once early data showed benefit, which constrained long term insights. Rare side effects required global surveillance with sample sizes in the millions. Manufacturing had to begin while trials were still underway, burning billions of dollars before approval. Public distrust, misinformation, and political pressure warped enrollment and exposure patterns in ways no model could predict. Biology is complex. Humans are complex. Pandemics move faster than clinical research.

This is the environment biotech leaders operate in. A biotech CEO lives at the intersection of uncertainty, incomplete information, and irreversible decisions. Few professions require integrating science, business, operations, and regulation under this much pressure. Every choice is a bet made with partial data. I learned this firsthand leading Healis Therapeutics, becoming the youngest cofounder and leader of a clinical stage neuroscience company. I had to make decisions that even seasoned executives lose sleep over. Which indication should we prioritize. How will regulators interpret our design. What signal matters most to patients, or to investors. There were no perfect answers, only judgments made inside narrow windows of time.

Leonard Schleifer of Regeneron captured the truth clearly: “In biotech, you have to be an optimist who is also terrified. You are betting on biology, and biology does not read your business plan.” The hardest working people in the industry are often working with the least certainty. That is why trials fail so often: not because leaders are careless, but because the information landscape is fractured and biology does not cooperate with human timelines.

Four forces make this work uniquely difficult. Biology itself humbles everyone who touches it. It is nonlinear, adaptive, and full of emergent behavior. Two cancer biologists may not even share the same conceptual language. Knowledge diverges faster than it converges. A CEO making a “scientific decision” is triangulating across dozens of narrow experts, each holding a fragment of an impossibly large system.

Then there is the market, where uncertainty meets capital. A biotech CEO must understand risk pricing as intimately as pathway biology. Every program competes not just with disease but with time, capital, and psychology. The information is probabilistic, opaque, and delayed. Even the best investors cannot truly know which drug will succeed. Volatility is extreme because the underlying uncertainty is extreme.

Operations add another dimension of difficulty. Clinical trials are miracles of coordination: dozens of sites, hundreds of patients, thousands of variables, all needing to align without error. Enrollment stalls, protocols are misinterpreted, manufacturing deviates, supply chains misfire. John Maraganore of Alnylam summed it up simply: “In biotech, the science will humble you, but operations will kill you.”

The regulatory pathway is a labyrinth of precedent and context. Success depends not only on what the data shows but on how it is framed, justified, and aligned with ethical standards. Every comparator, every endpoint, every phrase in a briefing document carries weight. You are not selling a product. You are earning trust.

This is why biotech is not “just another industry with normal challenges.” The layers interact. Biology, business, operations, and regulation each have their own data, incentives, and epistemology. When combined, the system becomes so complex it approaches chaos. No single human can hold all the relevant information at once. The bandwidth of the mind is too narrow. Expertise is siloed. The signal is buried in noise.

This is why over 90 percent of drug programs entering clinical trials fail. Not because teams are incompetent, but because the information is incomplete, the variables uncontrollable, and the underlying biology full of surprises. Even so, the stakes remain enormous. A successful trial creates billions in value and saves lives.

Both the influenza and covid pandemics revealed the same truth. Clinical trials are difficult because nature is difficult, and pandemics do not wait for us to get organized. COVID succeeded because decades of preparatory work already existed. The tools were built before the crisis.

The Role of AI

The question now is whether artificial intelligence can help. It can, but only if we are honest about what the problem really is. The main bottleneck in health is no longer discovery. We already have AI that can design proteins, search chemical space, and propose new molecules in silico. The bottleneck is delivery. Most drugs do not die in the lab. They die in the fragile, noisy, expensive process of proving that they work in humans.

This is where AI matters. At its best, AI is a compression engine for complexity. It can read every trial report, regulatory document, safety signal, and mechanism paper in minutes. It can model how a trial is likely to behave before anyone enrolls the first patient. It can stress test different designs, simulate enrollment patterns, and surface which subgroups are likely to respond or fail. It can coordinate thousands of decisions across endpoints, cohorts, comparators, safety monitoring, and site selection, decisions that today exist in separate slide decks and separate minds.

But AI by itself is not the point. A large model sitting on top of a broken process does not fix the process. If anything, it can make overconfidence cheaper. What we need is not AI as a toy or a chatbot. We need AI as infrastructure. An intelligence layer that makes the entire clinical system learn, not just answer questions one at a time.

Modern healthcare spends over eleven trillion dollars a year. Drug development alone burns more than one hundred billion dollars annually on clinical trials, with fewer than eight percent of programs reaching patients. That is not just biology being hard. That is a system that does not compound its own experience. Each company repeatedly pays the full price of uncertainty, rather than drawing down on a shared base of learning. AI is suited to change that. It is good at one thing humans are bad at: integrating massive amounts of messy information and extracting structure from it.

The next great company in health will not be another drugmaker or insurer. It will be the platform that makes medicine learn from its own experiments. This will also be the next great tool in our toolkit to address the next pandemic.

Clinical Trial Intelligence

CTI is needed now, even if the next major pandemic is not occurring now.

Clinical trial intelligence would sit across the life of a trial program. Before a trial starts, it would simulate different designs and flag those that are likely to fail based on similar programs in the past. It would identify which endpoints are fragile, which inclusion criteria are unrealistic, and where bias is likely to creep in. During a trial, it would track enrollment patterns, site performance, and data drift in real time, and suggest adjustments before problems become fatal. After a trial reads out, it would absorb the outcome and recalibrate its beliefs, so that every failure increases the probability of future success rather than simply erasing value.

This is not science fiction. The data already exists. Regulators publish decisions. Companies publish protocols, labels, and partial data. Trial registries track dates, locations, designs, and outcomes. Investors move billions on their interpretations. Right now, this information sits in PDFs, static websites, and human memory. Clinical trial intelligence is about pulling that entire universe into a single learning system that is trained on what actually happened, not just what was planned.

The impact of even modest improvement is enormous. For pandemics, this matters even more. When a new virus arrives, we will not have time to rediscover how to run good trials under pressure. We will need systems that have already learned from thousands of past trials in vaccines, antivirals, and immune modulation, ready to propose designs, anticipate pitfalls, and guide decisions in days, not months. The same platform that makes oncology and autoimmune trials smarter in peacetime is the one that will let us move at the speed a pandemic demands.

So the role of AI here is simple and ambitious. Make clinical trials self improving. Turn every protocol, success, and failure into fuel for the next decision. Give the hardest working people in the hardest industry a system that finally matches the scale and complexity of the problems they are trying to solve. When that exists, drug development will stop feeling like a casino and start feeling like progress.

Build Now

We cannot wait to build this when the next pandemic begins. The Gates Foundation and BioNTech did not know COVID was coming, but the mRNA platform built for HIV was ready when needed. That preparedness looked like foresight, but it was simply discipline. We know far more today. We know another pandemic will come. Climate change collapses the distance between humans and animals. Zoonotic spillover accelerates. Global travel speeds up transmission. The next pandemic could be fifty years away, ten years away, or already incubating somewhere we are not watching.

Clinical trial intelligence takes years to build and refine. Its value begins immediately, not only during a crisis. Oncology, immunology, infectious disease, and rare disease trials all benefit today. The same system that strengthens current development is the one that will pivot when the next outbreak arrives. The way mRNA pivoted. Only faster.

We build it now. Not during the crisis. Not after. Now, while we still have the luxury of preparation. Another pandemic is coming, and this time we already know it.

***

World Health Organization (WHO), “A World at Risk” (Global Preparedness Monitoring Board, 2019).

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM), “Biodefense in the Age of Synthetic Biology” (2018).

Nature Editorial, “Artificial intelligence and the potential for biological misuse” (Nature, 2023).